One of the more painful and costly steps along the way to an art show or convention for us, and other artists we know, is most always framing.

It seems that artists and artisans anymore, can be some of the most heavily exploited tradesmen when it comes to tools and supplies …and frames are certainly no exception.

Art supplies tend to be priced for Warhol-famed artists, design agencies with multi-million dollar clients, or students who simply have to have these things, and will have to take out loans and grants accordingly; Frames are often priced for artists of Ryden renown, or remarkably wealthy art buyers – factor in huge percentages for art sales through galeries, and it is no wonder that the gallery owner lifestyle of nice cars and sipping champagne contrast so beautifully with those of the artists supported: which I suppose for most of us… well, I don’t know how you get by, but lets say “robbing liquor stores for brush money” as a rather broad example.

And since for any show or convention it is good – if not mandatory, to have hang-able art. Many of us artists need to get creative if we wish to account for a 40% cut on sale price, and frames, without demanding a “Just who does he think he is?” sort of price.

One route, of course, is to gallery-wrap, or museum wrap paintings and giclees in a way that makes for a nice display without the need of a frame. Add a touch of color or a reflected image to the overlap, and such things do really tend to look very nice… though modern by default. Gallery wrapping and museum wrapping is available as an option for ready canvas through most any art supply provider, and having giclees stretched these ways is an option with most decent giclee printer. Doing this one one’s own is moderately difficult for gallery wrap, and strenuous for museum wrap – but by no means impossible.

If however your works are already stretched and mounted, with staples down the sides, or if they are painted/drawn/engraved on boards or paper and absolutely need to be framed – there are still a few creative, inexpensive, and simple ways to go.

One of which – if your works will fit standard frame sizes, is to go on “50% off!” weeks (we like to call them “regular price weeks”) to Hobby Lobby or Michael’s and buy their pre-made frames. Another solution of course is to go to places such as Target and Walmart and browse, looking for discounted frames that can be redecorated and customized to look nice… perhaps even to become works of art in their own.

One problem I have found with many of the ready-made frames (and even many custom frames), something I particularly dislike, is that I find many of these frames are either plastic, or low-grade wood, either made to look like better wood by way of plastic/acrylic veneers or overlay, ornate clay designs painted or coated over, or by other means. The most standard being those which are low-grade wood with the clay and paint overlay, which tends to chip and break in shipping… if it isn’t already broken in this way at time of purchase. The ones at non-art stores tend to be plastic molding with a plastic wood-grain sheet ironed onto them… again… trying to avoid that.

So, yesterday, after browsing many ready made frames at all the aforementioned stores, not finding anything I liked at a reasonable price – and finding mostly overpriced junk, I decided to try to make my own.

The first step was a trip to the hardware store for lumber, where I purchased four 6’x4″x1″ pieces of wood.. having struck out on all avenues in looking for a source for the wood strips framing galleries use. I’ll have to try that some other day.

So… wood…

I’d like to say I went for the fine cherry, a nice fire maple, or something moderately exotic – but what I ended up going for was a compromise.

At Home Depot, I found their “exotic wood” be be very exotically priced. I am used to prices being high on hardware at woodcraft – but Woodcraft’s prices certainly beat (by light years) the wood prices at Home Depot. I will have to remember: Woodcraft for wood, Home Depot for hardware.. but, of course it was late at night when we went… So Home Depot was pretty much where we were going for the lumber.

Pine being cheap and sub-quality wood, I looked to avoid that route – but in the good wood section I found what is called “select pine” – which is not quite gold-grade heartwood pine, but certainly not shabby construction-grade pine. It is nice and heavy, very dense actually, with a really fine grain and very tiny knots. I was rather surprised by how sturdy and dense it was, and at $4.19 a 6 foot piece – I decided to give it a try (and having tried it, I am actually quite happy with it).

[Edit] Having returned, and taking a closer look at Home Depot’s stock, I also found some really nice Maple there for about $1.40 a linear foot – still more expensive than the pine, about twice the price but certainly not bad. I also found cherry and red oak shelf capping for around $1 a foot, which I plan to use in future projects in place of the moulding below.

I also grabbed some decorative wood strips from Home Depot (sort of like above, but not the same design)… rounded and decorative on one side, flat on another. My plan is to use these to make the frames a touch more ornate. The price wasn’t bad.. $2.16.. Oh? Not “per piece” .. that’s a linear foot? Okay… I bought one six foot section. Also in my arsenal is some brass chain at Hobby Lobby (clearance priced)… about 120 inches of it. Home Depot had wood appliques – but their prices on those were ridiculous – I am supposing they were trying to get as much as possible out of cabinet makers. The things are incredibly cheap by comparison at Michaels… I’ll have to go there tomorrow, as they didn’t have them at Hobby Lobby and I wasn’t about to pay the Home Depot price for them.

So… first step: Cutting the wood

So… first step… measuring the wood.

These artworks are 5×7 inches. So, I want the inside of my frame to be about 1/8 of in inch smaller than that. Typically I’ll sit there and figure up the best mathematical formulae to get the perfect result – but diving right in, I simply measured 1/8 of an inch in, and used my 45-degree plastic triangle to mark where the first 45 degree cut would intersect that drawn line. I measured 6 + 3/4 (7 inches minus two times 1/8 of an inch) of an inch along that line, marked that point, and used the triangle to draw a line where the next cut would go.

From there I carefully and precisely made the first cut on the table saw, using my 45-degree angle-guide. Then I carefully and precisely made my second cut. From there it was just a matter of sliding forward my 45-degree guide, placing one edge against the (stopped) table saw blade, and lining up the straight guide to the end of that piece. After this I could just cut, flip the wood over, cut, and flip the wood over, making perfectly identical trapezoidal wooden pieces… my 7-inch sides.

After cutting the first two, just in case my angle guide was not entirely accurate, I matched up corners on the cut pieces, and checked them with my triangle, to make sure they were squaring up. They weren’t. So I made an adjustment of half a degree – and used these pieces over and over again until the angle was perfect.

I made 18 of these long sides, saving the first two ‘test pieces’ for use in making the shorter sides, since they were shorter after all the test angling.

Then I made the 5-inch sides, in the same manner as above, until I 18 of those as well.

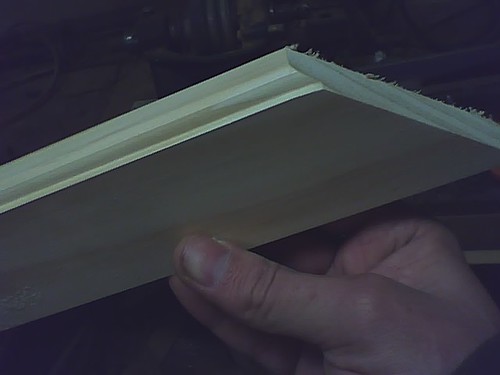

After this, I needed to make it so that the artwork could rest inside the frame, meaning that 1/8 inch recess (rabbet) planned for needed to be carved into the inside dimensions along the back of the frame-to-be. This is a good time to have a router (and a router table is all the better).

*If you do not have a router, which I am sure a lot of you may not, I would recommend starting with decorative beading (the sort of trim that, in a house, runs along a floor or a ceiling… available at most lumber stores). From there you can just build a simple square and square-edged frame for your work, with the inside of this being the exact size of your artwork (n0 need for a rabbet), but use the measuring and cutting steps above on the trim. The trim can be assembled on top of the box frame, glued, pressed, and clamped for a very nice look and sturdy frame. Those are the basics… I’ll go over that particular method in more detail, but it will have to wait for another post*

I used a router bit which has a curved into flat bevel, called an “ogee”. The flat edges would hold the artwork well, and the rounded surface would allow for the least amount of surface contact on the art side of the artwork.

I also used this same decorative “Ogee” bevel on the inside front as well. As a bonus, being the same on the inside dimension front to back, I could choose which side looked the best (according to the smoothness of the cut, the look of the grain, dents and dings, etc.) .

Having chosen which side would face front, I then took to beveling the Outer Edge on front side, giving it a smoothed and decorative face on the front (inside dimension and outside), but leaving the back flat and flush. For several of my frames, I also made the back outer edge beveled as well, giving the frames a nice rounded edge.

Once I had all my pieces done, I quickly sanded off all frayed edges and burs from my cuts, so the frayed ends would not get in the way of the next step: gluing.

Glue, actually holds more securely than nails or screws, if done properly, and of course keeps unsightly nails and screws from your frames. Such also negates the risk of splitting your pieces with such fasteners during the construction process.. which would be a terrible waste of all the work done up to now. There are special fasteners for framing (to be used later), but the glue is most important.. and will make that fastener step much easier if you choose to use fasteners.

I used a four-point box clamp for this. It makes jobs like framing, assembling stretcher bars for canvases, making boxes/cabinets, all go much more smoothly with these sort of clamps. If you don’t have them, I’d recommend using two (preferable four) bar clamps or pole clamps for this step.

Put glue along the ends of each piece, in thin streams, but try to cover most of the ends, and try as best you can to get the very edges of each end. Clamp them together, make sure all pieces line up square and even. Un-clamp and re-clamp if necessary… Such is much better than letting it dry uneven and having to redo this step or sand things down.

Let the frame sit this way for at least a half hour (preferably longer) before moving it. If it has only been sitting a half hour, remove move it carefully and then leave it be. You will however get better results if you leave each frame clamped for an hour or more. I plan to use 3/8 corrugated fasteners on each corner – they aren’t completely necessary, but they give a bit of added peace of mind to neurotic people such as me.

Next steps – added (wood) decoration, staining, added decoration (metal), placing the artwork, hardware (for hanging).

(Next installment)