I’ve heard enough from friends, colleagues, and others that I tend to go a bit overboard when it comes to my possibly overboard concern with quality when it comes to imaging and printing.

I spend a *lot* of time researching this, trying to find new ways to get better results, and to have more control over the process, especially since my move to Michigan, where high operating costs for businesses and a lack of local money have led to available services being less than stellar, if available at all. I have spent days, and days, every few weeks, just doing web searches, sending emails, making cold calls, and trying what few services I find here… and though I have managed decent results, they have come through much supervision, and the asking of many questions I would not have known to ask 10 or even 3 years ago.

Chances are, that if you do not live in a major city with a thriving art scene (if there is such a thing in this day and age), and if you are an artist trying to get prints made, you have found yourself frustrated with at least one aspect of the process.

Though printing for giclees is easy enough to find these days, in the most common of places, the imaging part is the absolute hardest to nail down, and the most important – because once you have sold the original painting, unless you have visitation rights in your seller’s agreement, you won’t get another chance.

There are a number of great digigraphic or reprographic places abroad. In Cincinnati, I had access to Queen City Reprographic, as well as the imaging person/photographer for the Cincy Art Museum, and the University of Cincinnati print lab. In Boston, I had access to Parrot Digigraphic in Billerca MA with their huge 72-inch scanner, and Ditto Editions in Salem MA with their 120MP Seitz camera setup (though they appear to have moved to New Hampshire) – but no longer living in the area, as amazing as these places were, there is the cost (and fear) involved in shipping a painting that has not yet been imaged many states away… and having to work by mail for proofing and other such services. A broken or lost painting can’t be imaged, so the fear of being forever screwed drives me to always look for local services if I can.

If you have $50,000 or more laying around for a Seitz camera setup, or $100,000 for a huge scanner (and recommended maintenance plan), you probably aren’t reading this anyway, and don’t need to. I’d think your time is worth enough that you’d rather outsource this work to a premium imaging company (as listed above) – So I am going to skip past those aspects of the process, and go directly into steps for the rest of us:

Step 1 – What Am I looking for?

This is pretty important. If you don’t know what you want, you won’t know whether you are getting it, and you’ll frustrate yourself and everyone you deal with, either in not knowing what to ask for, or finding that what you get is just not good enough.

— Actual size, in 600 DPI (preferable), 400DPI(still good), or 300DPI(acceptable). Sure, the human eye sees at 300 DPI, but consider that you might want to make prints larger than the originals, or highlight specific parts. Also consider that printers are getting better and better every day, as are papers, as are inks – and that if the result is a higher resolution, one might appreciate being able to take a magnifying glass to the print to see how great it is. Or, you may, like me: I am the sort of person who can read the microprint on a 20 dollar bill… I may not be able to see a tree at 20 years, but that is a product of being so detail-oriented. I put in details I can see that most others need a magnifier for, I even go so far as to put in details that *I* need a magnifier for, or details that I just *know* are there though I can’t see them. Most of all, the better your working file, the less fine details are lost to things like color adjustments and resampling through resizing. Don’t let people tell you that 150DPI is good because people are standing further away to view it – detail is lost, and they will not get the experience of looking at your work, but the experience of looking at a blurry version of your work. “Good enough”, is never, and will never be “Good enough”, else it need not be said at all.

— RAW or TIFF format. Jpegs don’t just lose data and detail every time they are opened and saved, the creation of a jpeg image alone is lossy. A group of eyelashes becomes a dark blotch of close colors that *look* perfect, until you campare.

— No adjustments. Every time a color adjustment is made, data is lost. A level adjustment brings you closer to the actual values, but causes colors to disappear. Every time an adjustment is made, close-to-white may become white, close-to-black may become black. Once they are gone, they are gone, and there is no processing you can do to get them back. It is always good to have an unprocessed image to start from, and always go back to that image if you need to make changes in brightness/color/levels.

— Quality. A 600DPI image makes no sense if it is 600DPI of blurry or 600DPI of blocky color.

Local Services

Calling or emailing in detail can be important here. I tried the universities first, hoping that they had for-pay services for non students, or that maybe I could put their students to work using the college’s equipment. It may work for you, but here, I couldn’t even get as far as finding out for certain what equipment they had on campus.

Then I turned to the local arts organizations, called a number of galleries, and asked what few local artists I could find what services they used. The answer was a resounding “uuuuuhhh?”.

When it comes to local artists, especially in mid-western cities, I’ve found that a lot of artists don’t even sell prints; Hell some don’t even actually produce artworks, or do anything more than sporting a goatee and adopting a highly-liberal point of view. Most functioning artists however are in the business of catering to galleries and coffee shops, who, since these places desire artists who can produce 20 or more artworks in less than a year, stick to artworks they can create in a single night… or several a night – which aren’t exactly the sorts of works that require printing. These sorts of works go to people who want an original, of certain colors or size, for $80 or less, to hang over their couch or in a closet…. or just to people who want to support budding artists… they tend not to do well as prints, especially considering that a person could just pick an original out of a bin.

Out of over 100 printing/imaging/reprographic places I contacted, only 10 said they were able to do this sort of work in house.

Of those, most were sort of scary – either for not having a grasp of the scale, or having a “sure, we’ll give anything a try” attitude about it. Not a one of them had a Seitz setup, or a large flatbed scanner (though one claimed to have a large enough flatbed). Some offered to use a 10 (or less) MP camera, some actually thought as far as to offer to take multiple photographs and piece them together (The latter, though ill-equipped I think might have actually known what they were doing, and *could* possibly have come up with passable results).

I went with the one who claimed to have a big scanner. The results were decent, save for some scan lines which I removed in photoshop, and the price was low (probably because of the scan lines). The color and brightness were the absolute best for adjustments – raw and untinkered with, with a broad range of values to be adjusted, just the way I like it… no data lost. When I walked into the back of their shop one day to see my painting being pressed against an 11×17 inch Epson scanner, I felt a bit betrayed, but continued to use them until that employee moved on (being mindful to remove my paintings from the canvas stretchers so they could scan without potential damage). After he left, the workers were less capable of getting me the results I wanted, and the new inconsistent pricing came straight from the “USS Make Shit Up”, so I started into the adventure that is….

Imaging At Home

Part I Scanning:

Scanning Smaller Works (under 11×17 inches):

I have a scanner that I bought through Sam’s club (I actually bought my membership specifically because the cost of the scanner+membership was $5 below buying the scanner elsewhere); The scanner is a Mustek A3 scanner (11×17 inches). They sell for about $199 including shipping most places you find them. I bought mine for $142+$7 S&H through Sam’s. The colors pretty much dead on, straight off the scan, and the detail is superb. It also plays nicely with photoshop and has the best import GUI I’ve had short of an Epson professional scanner ($thousands for a tinier scanner).

Until I broke it (I’ll talk about that later), I’ve always used this for any work smaller than 11×17; I have however found (in a moment of need) that Fedex/Kinkos has a flatbed 11×17, and will scan for under $2 a scan at any resolution you want. I tend to go for 600DPI for all my pieces, big or small. I know the human eye sees at 300 DPI… but I detail my paintings and other works so deeply, that printing larger than the original is sometimes desirable (plus: my tendency for quality overkill).

I think Kinkos $2 a scan is a pretty good deal. The scans come out quite well (but may vary at different places and with different employees). It is still always good to have your own scanner at home, in case your local Fedex is not staffed with adept people, or for scanning at 3AM.

Scanning Larger Works (above 11×17 inches)

As for scanning larger pieces with the A3 scanner, the biggest problem is the scanner’s “handy” beveled recess (the dip in the tray that holds papers in place). If your piece is bigger than 11×17 inches, it will sit away from the glass, and you’ll not get a good scan – it’ll be hella blurry, with colors shifting greatly from one edge to another, and utterly useless.

Is it on Canvas?

If you are so inclined, if your painting is on canvas, you can pull the staples from the back (or sides for cheaper ready-made canvas), and scan the piece in sections:

— Varnish can really help things, or really mess things up. If you have already varnished the piece, especially if it is a glossy varnish. Think of varnish as a lens. Not only does it increase the distance between the scanner glass and the actual artwork, but if your varnish has a brushed texture, you may get better scans in one direction than another, because such “polarizes” the piece. If I *have* to varnish before scanning, I brush the varnish in one constant direction, and scan in a way that the scanner arm is moving *with* the “grain” of the varnish. If I ever *have* to varnish, it is typically because I find that certain spots of paint are more flat or glossy than others, and I do so to even out the sheen painting-wide. A flat varnish is preferable, satin is a runner-up, and the thinnest coat possible.

— Keep in mind the most important thing when scanning in pieces is making sure all your scanned sections are square with the others. If they are off, when re-assembling in Photoshop, it is difficult getting that 0.02 degree tilt from one piece to another and making them all line up. If you *have* to rotate pieces in photoshop, don’t think rotating with the mouse will do it: use the numeric rotation (if you have gone to image:rotate, you’ll see a text box in the toolbar the top of your screen where you can enter numeric values). Be sure to zoom in and look it over from one corner to the next, to make sure it looks right (full view lies).

— Don’t rely on the photomerge tool, especially if your pieces are highly detailed. Photomerge is plenty good enough for assembling photographs for novelty’s sake, not for art.

— You may need to adjust levels from piece to piece to get them to match up well in color and lighting.

— Make sure each scanned section has at least an inch (or two) of overlap with the next so you can get rid of the edges, which tend to be shifted in color slightly due to the bevel.

— Turn off all lights in the room before you hit ‘scan’ (you can of course turn them on again in between scannings). Outside light can bleed in at the edges of your work, or through your work and make the pieces inconsistently colored/valued.

— A higher bit rate (8 bit color, 16 bit color, 32 bit color, etc), means more colors on the pallet, meaning smoother transitions between colors and values. Higher bit rate is good (though it greatly increases file size).

— Always save one assembled version that has no color/brightness/levels modificatons, and save it in TIFF (lossless format). You might need this if you decide the prints are too light or too dark.

— Always make adjustments from the original lossless and unmodified source. Every time you make color adjustments, data is lost, and your work drifts farther and farther from the original. Also, every time you open and save a Jpeg, it decays (loses resolution).

Is it on a Wood Panel?

If your painting is on a wood panel (or similar surface), this gets tougher (you’ll still want to read much of the above about varnish and whatnot). There is no amount of strength you can apply to put the board flat on the scanner, and you’ll break the scanner long before that. Even with an un-beveled scanner (like some Epson models), you need to be mindful that the board is probably not perfectly straight – press accordingly (but try not to break your scanner in the process).

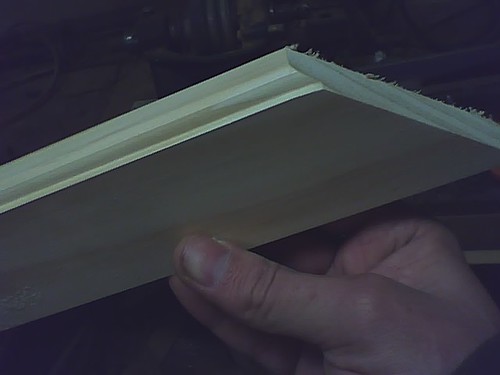

I modified my 11×17 inch scanner so I could scan paintings on wood panels. I did so by

(0) **read this entire thing before you decide whether it is a good idea**

(1) carefully removing the glass. It isn’t easy. It is held on by some *very* sticky stuff. I used an old iron on the glass side to make the glue “melty” enough so I could pry the glass loose. I thought I was going to keep the glass, so I put cloth between the iron and the glass to keep from scratching it.

(2) carefully removing the calibration strip from the glass (it looks like a bar code, and lines up with the scanner arm’s starting position)

(3) built a wooden box to hold the glass nice and level.

(4) taped down the calibration strip (face down, tape on the blank side, calibration strip on the top of the glass)

(5) repositioned the box with the glass until the calibration strip was being read properly

it isn’t as much rocket science as it would seem, except for the last part (so read this in full before taking your scanner apart):

— The scanner arm has a bit of spring to it so it always meets the glass, so getting the glass “close enough” to touch the arm, is good enough… no microns of distance/precision to worry about.

— The calibration strip needs to line up pretty perfectly, but if you make it so the glass/box is just loose with the scanner body sitting below, you can move it around until you get a good scan – then secure the box in that position with tape/nails/screws.. whatever.

— The glass *has* to be the same thickness, optical quality (normal glass has a greenish tinge that can throw off the color calibration), and *tempered*. In most cases, the only way you’ll get a 1/8th inch sheet of glass tempered is for it to be chemically tempered. Why not use the sheet that came with it? Well, *that* glass is made to be secured by sticky stuff, and is typically just microscopically wider than the scan arm that needs to move against it. So, making a support for the glass that won’t get in the way of the arm is difficult to impossible.

.. That last part is what got me. Though I *have* found places that will make the glass, it is around $100 to $200 #realartistsdonthavemuchmoney, so I am making due with the original sheet… which teeters delicately on .01 millimeters of metal bracket edge, which the scan arm occasionally gets hung up on.

The FrankenScanner (above). It works… but that is all that can be said about it. The glass, which I secured with two-sided tape, after a year, is pulling away from the remaining plastic bit. So, now anything with any weight causes the scan arm to freeze. I’ll need a new scanner… but I’ll probably rebuild this one as originally planned (diagram below) once I get the chemically tempered glass I need.

Frankenscanner 2 (Bride of Frankenscanner),waiting on a sheet of tempered glass. The nice thing about this way of doing it, is that the glass and box can be as big as I want them to be – lending to a better support area for large paintings. I’ll probably make some brass bars on hinges up top for reference/alignment… something I can swing down to match up with lines I’ve drawn on the back of the piece, for better squaring (not included in diagram).

(yay!) Out-of-the-Box For Wood or Canvas: The Scanjet 4670

(boo!) Discontinued

For scanning large items, especially if on a wood panel, you might be better off finding an HP Scanjet 4670. Unfortunately they are discontinued, because marketing gurus and management are typically idiots, and don’t know *who* to market a good thing to in order to make it a good thing.

I found out about this 4670 scanner, which can be laid with its nice flush surface down on a large object, through my friend and colleague Brigid Ashwood. I just ordered one days ago, but from what she has told me, it does a pretty damned good job and is a godsend (for all of the reasons outlined above). You can typically only find them used – try Ebay. This week, I’ve seen three in box sell for $103 (plus $36 shipping).

I plan to buy another of these as a backup BTW… so please don’t buy all of them.

Photography

Long have I waited for digital cameras to be good enough for this. I waited for cameras to get up to 7 MP, then found out that was not good enough, then 10MP… still not good enough… then 14MP… Now Nikon and Sony have 24 MP cameras out – which are good enough for 18×12 inches at 300 DPI… which really, is still not good enough.

I realized this lately, when I got an incredible photographer, both in skill and in talent, to photograph my pieces for print. The images are amazingly crisp and perfect in color, but at 12 MP, they will never be so crisp that they can be printed at 36×24, especially with all of the detail I put into my works.

It takes 25MP to equal 35MM film, 100MP to equal medium format film, 500MP to equal large format film.

If you are waiting to be able to do this in one single shot, you might want to just give up on digital for now, and try to find yourself a good medium-format film camera, or a photographer who has one. Just be sure you also have the means to scan the negatives (or a photo lab who will scan them *for* you).

For the rest of us, taking multiple shots in order to make one image.

It *can* be done, no matter how few MegaPixels you have – just how many individual pieces/shots you need depends on how great the resolution is. Another important part is realizing that moving the camera is bad, and why (outlined in the list of caveats below).

— Don’t let *just* MegaPixels dictate your decision though. Recently I found an amazing 14.5 MP camera with a great lens, and true SLR format for $149. The downside is that it saves all images as Jpegs, which are instantly lossy with bits of detail and nearly matching colors blurred together in chunks.

— Make sure your camera saves in either TIFF or RAW format. This is more important than MegaPixels. I switched back from the 14MP to the Canon 10MP because of the Jpeg thing.

— Don’t use a point and shoot. Don’t use a macro lens. *All* lenses round out at the sides (meaning a square will be “bowed” at the edges), and the best you’ll possibly get is a “true vision” or 50MM lens.

— Don’t use digital zoom. That just uses computer logic to try to translate an image more crisply from smaller pixels. A computer cannot know to make a row of eyelashes from a black blotch – all it does is to crisp up the edges. Make sure your zooming in or out is all optical.

— Use a Tripod! This should be a given, but I am saying it. Camera shudder is your enemy.

— Use the timer, or a remote, or a cable release. If you click the button by hand, your camera will move and shake, no matter how good your tripod is.

— No on-camera flash! Seriously… flash for any photo subject is best as a last resort, and terrible for capturing a painting. This isn’t a sporting event or a party, you don’t need to be mobile. You’ll get hot spots, color shifts, and maybe glare out your image altogether if you use a flash. Use stationary lighting. It isn’t like you need actual 200 watt or 500 watt lights anymore, there are low-wattage equivalents everywhere. Stationary lighting allows you to see your shot exactly as it will shoot.

— Lighting: You need a natural daylight spectrum. *but* you want it to be controlled and constant, since you’ll be trying to put multiple shots together, and you want them to be identical in lighting, distance, and angle. You can buy a 200-watt equivalent (40 watt actual) daylight spectrum bulb for $6 to $9 most anywhere online (try google shopping). You’ll need several of them.

— Lighting stands/reflectors are highly recommended. It’ll save you the frustration of gathering lamps from the household and propping them up on books and moved furniture. You can use extra photo tripods or tall lamp posts and utility light reflectors, or pie plates if you need to improvise.

— Put one light on each side of the camera, at 45 degree angles, and slightly higher than your painting. If the lights are in front of you, keep them far enough away from the camera that the light isn’t bleeding through from the sides of your shot. Also make sure there are no hot spots/glows/reflections on the portion of the painting you are shooting. Move the lights around until the *portion* of the painting you are shooting has just the right amount of light. Indirect lighting is absolute best for avoiding hot spots, so don’t point the lights *at* the painting. Try moving them higher, lower, more outward, more in – maybe even experiment with bouncing them off white surfaces (walls, ceilings, tacked up sheets) to soften them up and spread them out. Bouncing the light is of course best. If you have reflectors (umbrellas) made for this, even better.

— If you have a camera with light metering and related controls, and can set your white balance manually, do it. A *lot* of the fine-tuning can be done through just adjusting these levels.

— Set your camera’s ISO to its lowest setting for best image quality.

— Set your aperture to between f/5.6 and f/11 – this allows you the best sharpness, while still allowing some room for minor adjustments.

— Shoot each portion without moving the camera. If you move the camera, you will never have the lights and painting the same distance and angle from shot to shot, and you’ll lose all consistency. Instead, move the painting a foot or two to the left/right/up/down until you have all parts photographed.

— If you are good with building things – for this, I’d highly recommend making something where the painting can be mounted securely to a flat and straight board, and where that board can easily be shifted up/down/left/right. You can use drawer slides, or brackets, or just screws (screwing board A to board B, unscrewing it and re-screwing it for each move), or you can go more advances and use gears and cranks. I am using the low-tech boards and screws method (but on the lookout for old window cranks and worm gears so I can do the latter). Paintings on boards, or on canvas, when unframed, tend to be slightly bent or bowed.. so just hanging it in different places on the wall might not do.

— Make sure (as with scanning) your photos have a bit of overlap – not just so you can crop off the edges and keep the center (which will be slightly rounded), but so you can more easily line up one piece with another.

— do not pack up your lights and painting and camera. Leave it where it is for now. You may need to come back to it later.

— Again, do NOT use photomerge.

— Put each piece in its own layer, move them into place, crop away some of the edges of each (but leave yourself some overlap), make minor color adjustments to each piece if needed. Once all pieces are properly aligned, use your eraser on the edges of each overlying piece to ensure an extra smooth transition. Once you are certain everything is going to meet up perfectly, merge them all together. If there are any parts you aren’t altogether happy with, go back to your camera setup and re-photograph that piece or section.

I’ve found that at 12 megapixels, I can get a 36×24 inch painting with 15 photos (5 photos wide, 3 photos tall). If yours needs to be printed smaller, you can of course get away with less photos.

If however your painting is less that 11×17 inches – this is silly. Take it to Kinkos and scan it, or buy an A3 scanner.

Some Last Little Tips:

— Calibrate your monitor. There are free apps for this such as Calibrize. I have mine calibrated for perfect colors and perfect web brightness/contrast, and then have my *mind* calibrated for perfect print. I *know* how much lighter the images need to look in order to get them to print as they are seen on my screen, for each and every printer I use, and I know this through trial and error.

— Don’t use “Image:Adjust:Brightness/Contrast”, use “Image:Adjust:Levels”. Move the triangle on the left over a few points so it is nearest to the first spike (black values), slide the middle slider right a bit to make the mid tones richer, do not slide the white point (far right), ever if you can avoid it unless you want to forever wash out your near-whites. Don’t take this as law though: Experiment, and always do what is best for that individual piece. Most importantly, do not save over your original file, or you’ll be sorry when you need to adjust these levels for a new printer or printing medium.

Conclusion

1) Scan small stuff at Kinkos, or buy a Mustek A3 scanner.

2) For large works, if you can get one, grab the scanJet 4670 from Ebay or elsewhere – or go the photography route and (recommended) build a rig for photographing paintings in pieces. Also, don’t forget that you can (carefully) remove canvas paintings from their stretchers if you must scan on a standard scanner.

3) If you can, pay the man (time is money) – If you are not hell-bent on full control, and have the money, and can find a good local service: Use them. This stuff is a huge headache, and you can use all the hours you’d spend on research, practice, fine tuning, and execution on making works that would be worth whatever you are trying to get out of paying. Reasonable imaging for a painting is $300 for something in the 36×24 to 48×24 ballpark.

I’d recommend against proofing ($200 or more additional) – do the color adjustments at home, make crops of your image (saves money) with different color adjustments, and get those printed. I have several versions of the most crucial 8×10 section of a painting printed in my first try. Be sure to label each try, so you know which was the one that looked bright on your screen, which was the one that looked dark, etc… Hold these printed bits up to the original and compare.

Once you have this down, use the same printing company for as long as you possibly can… Once your prints are perfect, buy all 20,30, or 50 limited editions of that print that you plan to offer – and store them in a flat file or a large flat box. Why? Because a printing company’s printing profiles can change, or maybe the day you order print #27 of 50, some nose-picker replaces the worker who used to print your works perfectly. Maybe they change inks, or canvas type… either way, that Limited run you thought you could run one at a time (the benefit of digital offset world), is screwed… and by the time you make adjustments to account for the variation, you are sitting on three or four prints you can’t (in good conscience) sell.

I’d go into recommended printing companies,things about color profiles and other such things here, but that would make my summary/conclusion long. That will have to wait for another post. Stay tuned.